Hoosier Canal Mania

“It was the Internal Improvements Act of 1836, which appropriated a time-sensitive 6 million dollars for canal building and other improvements, that launched Indiana into the Canal Era.”

Following the success of the Erie Canal from New York to Buffalo, Indiana’s leaders had a dream of digging a statewide network of canals. Several attempts were made before and after Indiana was granted statehood in 1816, but all failed for lack of funds. The first Hoosier lottery was conducted in 1819, with the hope of raising the necessary funds to build a canal around the Falls of Ohio, but the game garnered only $2,536. This was considerably shy of the dollars needed to begin construction. It was the Internal Improvements Act of 1836, which appropriated a time-sensitive 6 million dollars for canal building and other improvements that launched Indiana into the Canal Era.

Several weaknesses were inherent in the young state’s implementation of the congressional act enabling the waters of Lake Erie to unite with the Wabash. The first was allowing the purchase of Federal lands with only 1/7 of the cost in cash. The remainder was due in six equal annual installments. Because of the insufficient influx of cash, the State found it necessary to borrow $600,000. As sectional jealousies surfaced, legislators were lobbied to include their constituencies in the public works. Consequently, only seven counties in the state were not included among those intimately touched by the proposed improvements scheme.

Only two canal systems were successfully completed in Indiana: the 101-mile Whitewater Canal from Hagerstown to Cincinnati, and the Wabash & Erie Canal from the eastern state line near Fort Wayne to Evansville on the Ohio River. The Wabash & Erie connected with canals in northern Ohio, which then joined the Erie Canal at Buffalo, New York. At 468 miles in length from Toledo to Evansville, it was the largest fabricated structure in the United States. Furthermore, the Wabash & Erie Canal was the second-longest canal in the world. The Grand Canal in China is the longest.

The Canal Era Begins

On February 22, 1832, the Wabash & Erie Canal was started in Fort Wayne, IN, on the anniversary of George Washington’s birthday. Once completed, it connected Toledo, OH (Manhattan), and Evansville, IN. A July 4, 1843 grand opening celebrated its connection of Lafayette, Indiana as the head of steamboat navigation on the Wabash, with Toledo, Ohio, on Lake Erie. The Toledo to Lafayette portion was in service longer than the southern section.

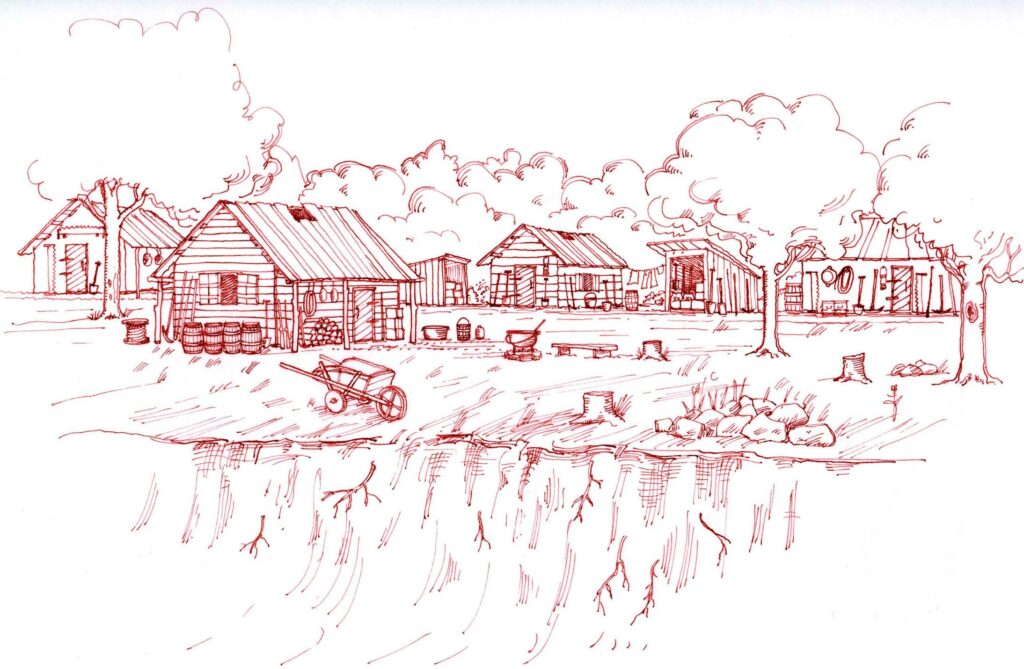

In Indiana, the Canal was built mostly by Irish immigrants using shovels, picks, wheelbarrows, and the horse-drawn slip-scoop. By 1837, there were 1,000 laborers employed on the state’s canal system. Accidents, fever, cholera, fights, and snakebite exacted a heavy toll on the workforce, many of whom were buried as they fell on the towpath. It has been reported that the toll in lives from the building of the Canal was one person for every six feet of completed Canal in the forty-mile stretch between the Indiana / Ohio state line and Junction, Ohio. This figure, however, has been vigorously contested by some canal historians.

Locks, dams and bridges were built to allow for topographical differences along the route. American ingenuity rose to the occasion as unique engineering solutions were found to meet the particular challenges presented by Indiana’s geography. Swing bridges, systems of counterweights, tumbles, dams, locks, and development of concrete that would harden beneath water were part of the canal builders’ experience.

Local engineering marvels included a swing or pivot bridge on Franklin Street / Bicycle Bridge Road; the Carrollton drawbridge, which allowed steamboats access above and below it; the stone Burnett’s Creek arch, reminiscent of Roman aqueducts, up the towpath from Lockport; and the 170-foot Deer Creek dam and towpath bridge southwest of Delphi.

The Canal reached Logansport in 1838 and Delphi in 1840. An article from Cass County historical records declared, “The whole town turned out to see the first boat come in on the ‘raging canal’ drawn by three mules—made 5 or 6 miles per hour.”

Traditionally 40 feet wide, parts of the Delphi portion of the Wabash & Erie Canal were 80-120 feet wide due to a natural slough, called the Bayou of Delphi. This wider section, which includes the waterway through Canal Park, lent itself as a natural port and a fine area for warehouses, piers, loading, unloading, and passing water traffic.

Within Carroll County, a dam across the Wabash River from Delphi was begun in 1838 and finished in 1841 with a steamboat lock at Pittsburg. This thriving town was platted in 1836. The extended slack water enabled canal boats to cross the Wabash at Carrollton, travel southwesterly along the lake for two and a half miles and re-enter the Canal at Paragon, a mile above Delphi. It is often referred to as the Great Dam, because the engineer proclaimed it the largest dam built in Indiana, if not in the entire West! After the canal era was over, a group of disgruntled citizens blamed the dam for flooding in the area, and with a mixture of malice and blasting powder, took Fate into their hands. The dynamiting of the dam on February 9, 1881 ended Pittsburg’s economic boom as well.

“In Indiana, the Canal was built mostly by Irish immigrants using shovels, picks, wheelbarrows, and the horse-drawn slip scoop.”

Canal Commerce

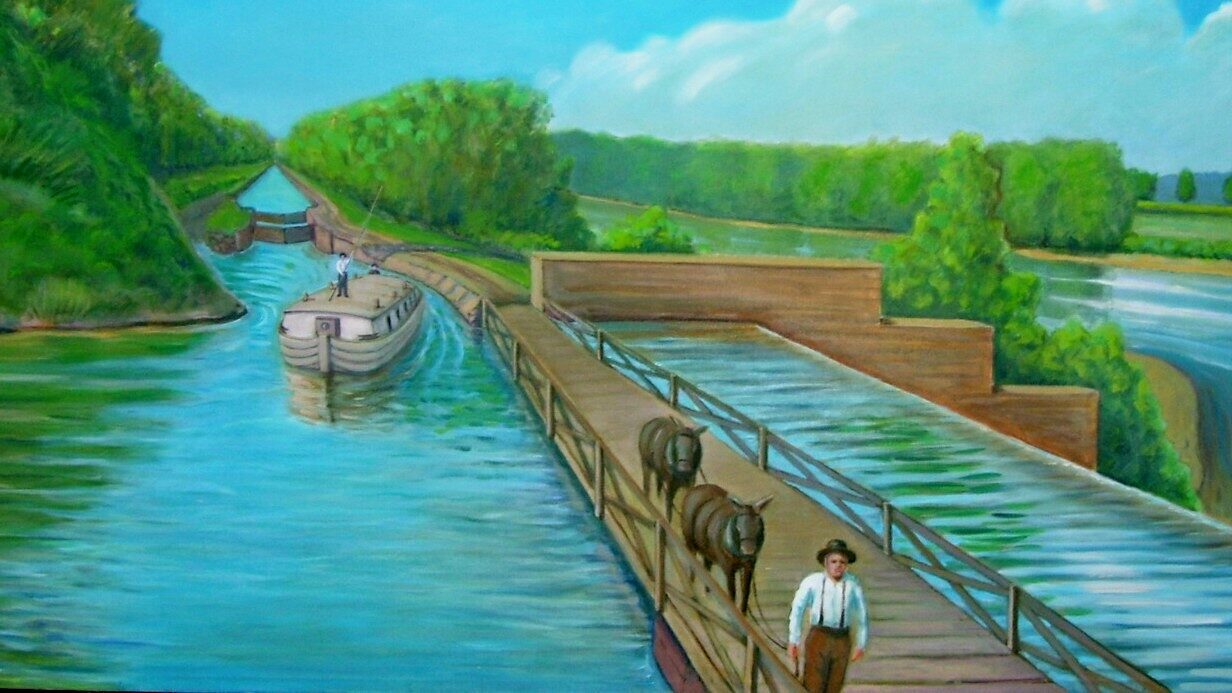

Several types of boats travelled on the canal, but the two used for business were the packet and the line boat. The packet was primarily used for transportation of passengers while the line boats hauled freight.

Both packets and line boats were decked in hues of green, yellow, brown, red, white, or blue, complete with coordinating panels and window frames. The packet Silver Bell was painted silver and drawn by a matched team of gray mules in silver harness. It was known for its tinkling silver bells and speeds up to eight miles per hour.

Barges were constructed of wood, which was in great supply throughout the region traversed by the “Big Ditch.” Farmers, loggers, wagon makers, and others made use of the Canal with their own canal boats, transporting goods to market and bringing back items on their return. Exports from this area included grain, lime, logs, pork, and whiskey. Numbered among the imports were coffee, salt, manufactured goods, and settlers.

The Canal held great appeal with the general populous over railroads because the common pioneer could construct a makeshift canal craft with the tools at hand. Rail cars could not be easily fashioned and were often built near foundries, purchased, and shipped by water inland. The Wabash River, which had long been a native thoroughfare servicing the inhabitants of the area, became alive with water traffic and related businesses.

Taverns, akin to hotels today, sprang up at regular intervals, spaced the distance it took to travel in one day. Bedrooms were furnished with three to five beds. Curtains hung from the high posts, to be drawn for privacy at night. Newspapers were often laid on the tables regardless of how old they were, often with an accompanying admonishment to refrain from stealing them.

The traditional three to five mile-per-hour speed limit (imposed to protect the Canal banks from eroding) was neither obeyed nor adequately enforced. Packet boats were faster and they carried passengers, mail, and other time-sensitive cargo. Although there were clearly defined rules regarding speed, lock entry and departure, and tolls, these often gave way to the fighting prowess of the deck hands.

To be sure, speeding and fighting were not the only wayward pastimes practiced on the Canal. The ticket price on a canal boat typically included meals and a bunk at the rate of about five cents a mile. This figured out to be about a mile in twenty minutes excluding locking. Frequently, a pedestrian would wave down a packet at mealtime and jump aboard. At the announcement of the meal the cheat would consume as much food as possible within the 20-minute span, pay the captain his five-cent fare and disembark a mile from his original point of departure.

To appreciate the Canal’s impact on the population, consider that when the Canal began operations, Indiana had a population of 350,000. By 1840, it had 988,000. In 1835, Indiana counties bordering the Canal boasted 12,000 inhabitants and in 1850, 150,000. Just in the three years following the opening of the Canal from Fort Wayne to Huntington, five new counties were created along its route. During this time, many of the newcomers were people who were attracted by the boom and moved northward from southern Indiana.

During the harvest season, the Canal was an ideal means of transportation for extra crops and livestock. Good roads were non-existent, as much of Indiana was still a wilderness with well-established towns mostly on the Ohio River and along the Wabash and Whitewater Rivers. Before the canal trade opened, it was not uncommon that farmers received 10 cents a bushel for wheat or 45 cents a bushel if it could be transported to Michigan City. After canal trade was initiated, farmers earned a dollar per bushel. Likewise, the cost of imported goods dropped as transportation improved. In a matter of a few years, salt plummeted from 10 dollars a barrel to four dollars.

One of the most important uses of Carroll County’s natural resources was in the production of plaster and whitening products. Limestone was quarried from near the land surface and placed in tall kilns along with wood as fuel. The “burning” of the lime caused the rock to disintegrate. The final product was sifted, loaded in barrels, and shipped via canal boat to destinations such as New York City and New Orleans.

Delphi’s lime was much in demand because of its high quality and whiteness. It was used in plaster and mortar and in making whitewash.

Perhaps the largest industry along the Carroll County portion of the Canal was the Spears, Case, and Dugan pork packing and grain business. Next to Madison, Delphi was referred to as the “junior pork packing center of the West.” Delphi’s canvas hams were famous worldwide.

On a body of water designed to be virtually without current, the possibility of a catastrophic wreck with loss of life seems ludicrous, but it occurred. Having left Lafayette headed east, on the eleventh of June in 1844, the packet “Kentucky” was approximately five miles from Logansport when disaster struck. Most of the passengers were enjoying supper below deck when a break in a mill dam allowed the escape of a powerful surge of water. The wave propelled the small craft out into the muddy, flood-swollen Wabash where it was dashed to bits against trees. Killed in the incident were Mr. Thomas Emerson of Logansport, and Mr. J.A. Griffin of Fort Wayne. Although both of their bodies were finally recovered long after the incident, the body of a stranger traveling from Indianapolis was never found.

End of an Era

The cost of carving the Canal from wilderness and the expense of the waterway’s subsequent upkeep far exceeded the expectations and the funds set aside for the project. Unlike in neighboring states, most canal structures in Indiana were constructed from wood and they required constant repair. Indiana weather—floods in spring, drought in summer, ice in winter—hampered canal traffic and reduced anticipated revenue. The State of Indiana faced a staggering $15,088,146 debt burden before its 25th birthday in 1841. This resulted in the present provision in the Indiana constitution that forbids indebtedness.

Railroads gained popularity because they could run all winter and were not as subject to disruption of service due to drought and floods. One of the great ironies of history is that the slow-paced mule-driven canal boats transported the rails from foundries for building the railroads, which closed the chapter on the Canal Era by the 1870s.

Tradition has it that in 1874, “Keystone State” was the last boat to cross the Deer Creek towpath bridge adjacent to the Deer Creek Dam southwest of Delphi. As the rotting deck timbers gave way causing the towpath bridge and adjacent dam to collapse, both driver and mules plunged to their deaths at the outlet into the Wabash. As the water escaped the canal prism all the way to Lafayette, watercraft heavy with merchandise were stranded in the resulting mire. The era was over and the State auctioned off all the canal land.

Special thanks to former board member, Frances French, and Allen County historian, Tom Castaldi.